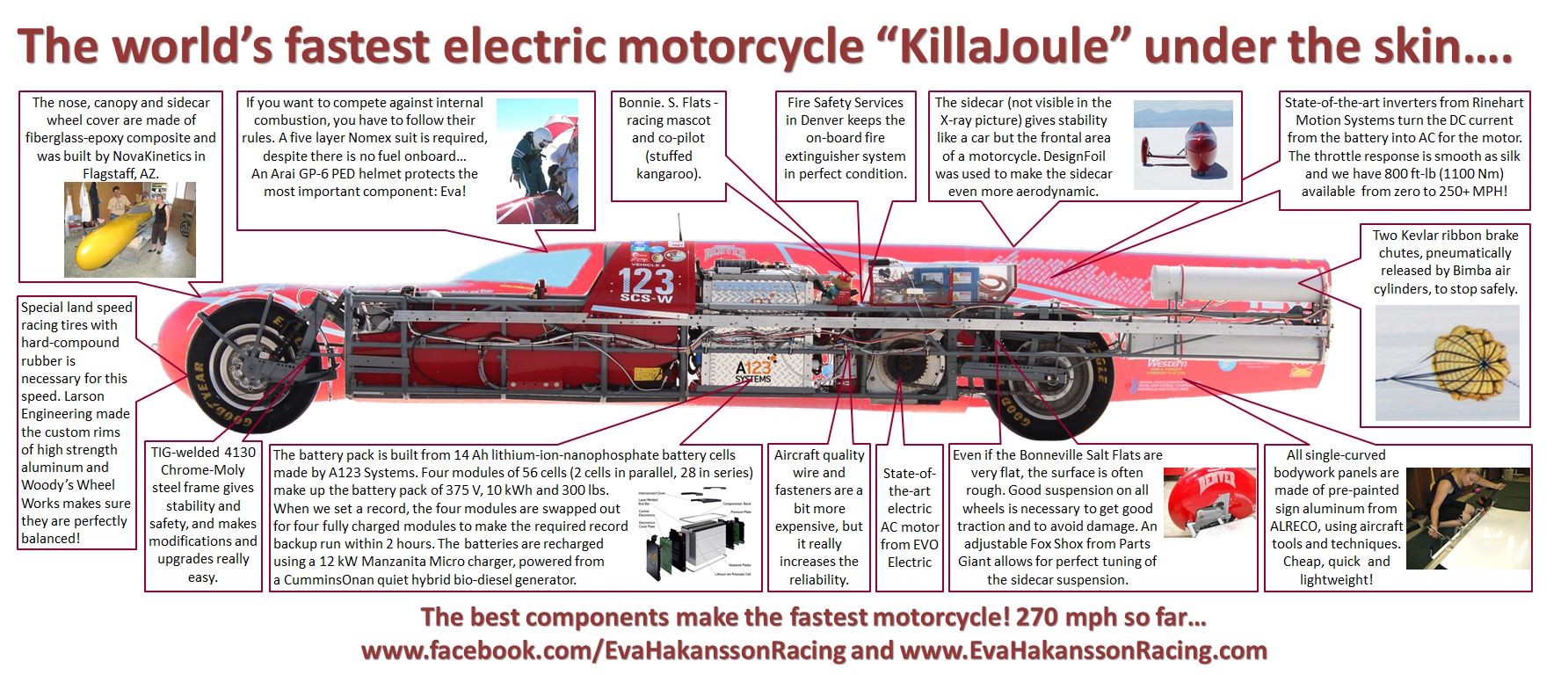

At 270.224 mph (434 km/h), the KillaJoule is the fastest electric motorcycle in the world. It has also made its rider and builder Eva Håkansson the world’s fastest woman on a motorcycle. But what makes KillaJoule so insanely fast? We are un-wrapping the bike and revealing all its secrets.

There are only three battery-powered vehicles that have achieved higher speeds and they are all four-wheeled cars: Buckeye Bullet 1, 2.5 and 3 which all have been over 300 mph. They were built by Ohio State University large student teams, and they have budgets that are at least ten times larger than the KillaJoule budget, if not a hundred times larger.

While speaking of budget, let’s start there. The KillaJoule is a private hobby project by the wife-husband team Eva Håkansson and Bill Dube’, built on a shoestring budget. It was built in their two-car garage over a period of eight years, working only evenings and weekends. Not including the thousands of hours of labor, the KillaJoule is worth about $250,000 in parts. About half of that value is from generous in-kind sponsors supplying parts such batteries, motor and motor controllers, and friends donating time and skills to help with bodywork, chassis and wheels. The rest of the funding comes from Bill’s government salary, since Eva until recently only receives small monthly stipend as a PhD student. About 80 % of the “blood, sweat, and tears” are Eva’s, as she prefers to explain it. That said, the budget is not one of KillaJoule’s secrets, it is one of its main limitations.

So how do you build a record-breaking vehicle on a shoestring budget? Well, you have to put in a bit of cleverness and a lot of “sweat equity” instead of money. These are the real “secrets”.

KillaJoule is also built with a mission in mind; that mission is to show that eco-friendly doesn’t mean slow and boring. This heartfelt cause makes it much easier to spend all your spare time and almost all your spare money on a project. We call it “eco-activism” in disguise.

Time-lapse video: After 2 months in a sea container coming back from the educational tour in New Zealand 2014, KillaJoule is in desperate need of some TLC. The humidity in the container combined with the residual salt from Bonneville hiding in every crevice, makes everything that can rust do so. Bill had to drill out one of the _stainless_ steel screws holding on the lower tail skin. Imagine of the screws were not stainless, we would have been drilling them all out…

It’s all about the batteries!

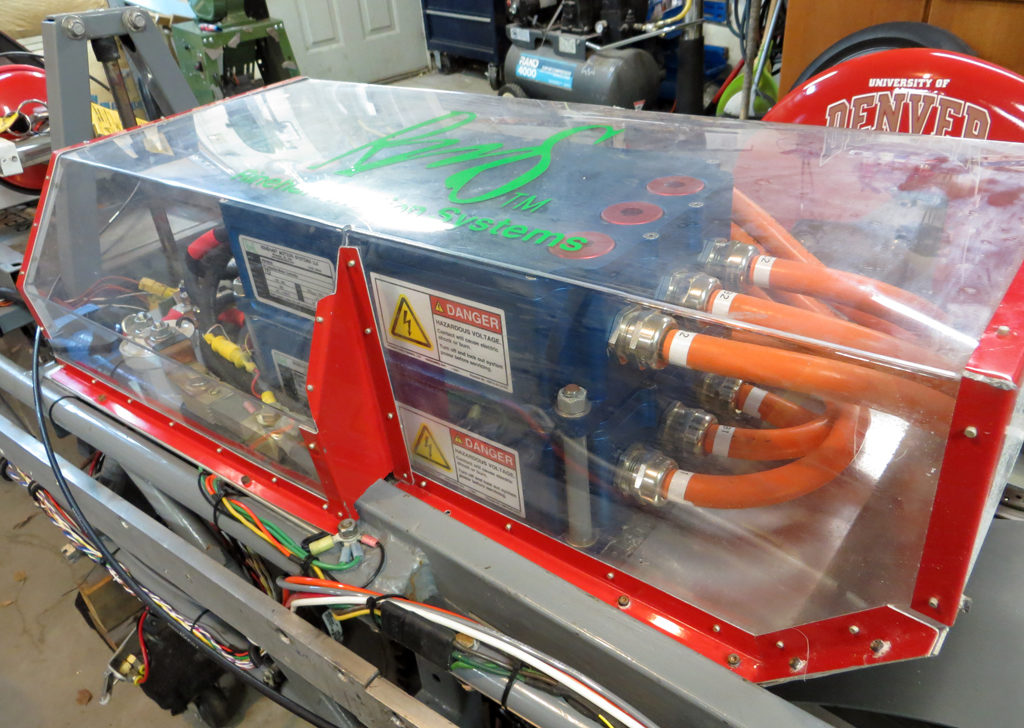

The key to setting world records are batteries. Without the right batteries, nothing else matters. KillaJoule is powered with A123 Systems Nano-Phosphate lithium-ion batteries. The battery pack is built from 14 Ah battery cells. These high-power cells are used in hybrid cars. Four modules of 56 cells (2 cells in parallel, 28 in series), and an additional module of 12 cells (2 cells in parallel and 6 in series) make up the battery pack of 400 V with a capacity of 10 kWh. The 300 lb (135 kg) battery pack can deliver over 400 HP.

The bike has two identical battery packs that can be swapped in about 15 minutes. When we set a record, the five modules are swapped out for five fully charged modules to make the required record backup run within 2 hours. The batteries are recharged using a 12 kW Manzanita Micro charger, powered from a CumminsOnan quiet hybrid bio-diesel generator installed in our trailer.

AC motor – the only viable option when racing on salt

KillaJoule is powered by an EVO Electric AFM-240 motor. It is a completely sealed, water cooled, AC permanent magnet axial flux motor, specially designed for motorsport applications. The motor is of a modular design with two rotors on the same shaft (there is also a smaller version of the motor available on the market that only has one rotor). Electrically, the motor is really two motors in the same case. Each “half” of the motor is electrically isolated from the other half and has three cables for the three phases.

The bike had originally two air-cooled “Advanced DC” motors borrowed from the KillaCycle dragbike. While open, air-cooled motors are perfectly fine on the ¼ mile dragstrip or on a paved track, it is not suitable for racing at Bonneville Salt Flats. Salt dust was sucked into the motors. The wet salt is conductive and the motors arced. That was the end of those motors.

Two Rinehart Motion Systems PM100 motor controllers convert the DC (direct current) from the battery into 3-phase AC (alternating current) for the motor. Each controller serves each “half” of the motor. If one controller for some reason would mal-function, the bike will still run on the other half of the drivetrain. This accidentally happened in 2013 due to a loose control wire. It was quite frustrating before we could find the problem. The Rinehart controllers are some of the best available on the planet. The motor controllers really set the throttle response in the vehicle, and the Rinehart controllers are smooth as silk. KillaJoule can be run perfectly controlled at any speed, it even has reverse. The reverse is used frequently in the pit area at Bonneville because the turning radius is very large.

Aerodynamics – making the smallest possible hole in the air

Land speed racing is all about aerodynamics. The smaller “hole” your vehicle makes in the air, and the slicker it is, the faster you can go with the same amount of horsepower. However, the vehicle still has to be big enough to fit the driver, so the width of the shoulders and the size of the head with the helmet set the minimum dimensions on the vehicle. At the same time, your drive train has to fit in the vehicle. You could make the vehicle larger and add more horsepower, but power is expensive. The drivetrain in the KillaJoule costs roughly $100-$150 per HP, or about $45,000 for 300-400 HP. Building a larger vehicle with more power was out of question. The solution was therefore to make the vehicle area as small as possible. It was built around Eva, which resulted in a maximum rider height of about 5’2” (158 cm)… Because of this, nobody other than Eva has driven the vehicle in a race.

Tires – keeping the rubber on the road at almost 300 mph

One of the biggest challenges going almost 300 mph is to transmit the power on the ground, and keeping the tires from flying apart. You cannot run any old tires at that speed. The KillaJoule originally used motorcycle racing tires. These roadracing slicks were good for just over 200 mph. During a run in 2012, the front tire started to delaminate, and it was just a matter of time before the rear tire would have done the same. The dull thuds and burnt smell from the delaminating front tire made for an “exciting” moment for Eva at 213 mph. The tire was still holding air, but it was definitely due for an upgrade.

The main reason the motorcycle tires failed was not the speed – roadracing motorcycles often exceed 200 mph on the straightaways – but it was the weight. A normal roadracing motorcycle weighs perhaps 500 lb (225 kg) with the rider. The KillaJoule weighs 1540 lb (700 kg) with the rider. The tires were loaded three or four times higher than they were designed for.

The only solution was to upgrade to real land speed racing tires. These are specialty tires designed for speeds up to 350 mph (560 km/h). The problem is that they don’t come in motorcycle sizes, only car sizes. That meant it had to be mounted on a 15 inch rim. There are no 15 inch motorcycle racing rims that will fit Suzuki GSXR 1100 hubs, which was the “donor” motorcycle that we originally took the hubs, axles and brakes from to build the KillaJoule.

The solution was to purchase dragracing car rims, cut out the centers and make custom hubs. The was a huge job, and we couldn’t have done it if Rick Larson at Larson Engineering in Boulder, CO hadn’t donated over 50 hours of time in his shop.

Choosing the right materials

Without a budget to pay for other people’s time, we had to build almost everything ourselves. That meant that we had to choose designs and materials that we could handle in our quite sparse machine shop, a.k.a. our two-car garage.

Anything really high-tech like carbon fiber composite was out of question. We opted for a tube frame of chrome-moly 4130 steel. We knew that the fastest motorcycle on the planet – the 376 mph (604 km/h) AckAttack – was using this design, so it had to be a good choice. We built all the suspension as simple as we could; a springer-style front end of steel and a classic twin coil-over shocks for the rear suspension. The clever sidecar suspension, also all made from steel parts that we could make ourselves, was designed by Eva’s dad. All the mounts for the drivetrain and for rider’s safety equipment such as seat belts were welded directly to the frame. A simple coat of brushed-on oil-based paint protects the steel from rusting. There was no budget for extravagances such as powder coating (it is also easier to make modifications and re-paint with normal oil-base paint, so powder coating was out of the question for that reason as well).

The fiberglass nose and sidecar wheel cover was skillfully custom-made and very generously donated by Jim Corning at NoveKinetics Aerosystems in Flagstaff, AZ. We built the rest of the bodywork from pre-painted aluminum sign stock using aircraft techniques. Bill had all the tools because he was once building an experimental airplane (which was sold to afford the big trailer for the streamliner), but he kept all the tools.

Read the rulebook…

…before you start to build! Land racing has strictly enforced safety and class rules. Countless of racers have had to turn around and go home after the technical inspectors pointed out that their vehicle would not comply with the safety rules. The KillaJoule is built exactly according to the rulebook, which makes the technical inspection on race day much less painful. The inspection is still stressful, however, as all racers fear they have overlooked or forgotten some vital detail. As a streamliner rider/driver, you also have to perform the so called “bail-out test”, which is something everybody dreads. For this portion of the inpection, you have to get dressed up in full race gear including fire proof suit, helmet, neck protector, gloves, and boots. You then get completely belted in with the canopy closed. The seatbelt in KillaJoule is a 7-point racing harness plus arm-restraints and leg net that keep your hands and feet inside the roll cage structure in case on a crash. When the inspector knocks on your windshield, you have just 30 seconds to get out without assistance of any kind. If you take more than 15 seconds, you will pass, but they will ask you to practice more. In case of a fire, you fire suit is only good for 45 seconds in direct fire, so it is easy to understand why all these rules are in place.

Speaking of competition rules, what kind of vehicle is KillaJoule really? Is it a car, a motorcycle, or something in-between? Well, according to international motorcycling competition rules, the KillaJoule is a “sidecar streamliner motorcycle”, it is “electrically powered” and runs in the class for vehicles over 300 kg (over 660 lb).

A sidecar motorcycle is defined as a vehicle that has two wheels in line, where only the rear wheel is driven and only the front wheel has steering. The third wheel is offset and has neither propulsion nor steering. It makes two tracks on the ground. In land racing, a “car” is defined as a vehicle that has four or more wheels, so KillaJoule is clearly a motorcycle. However, if I would add another sidecar on the other side, it would then become a car.

It is all about teamwork!

You can prepare for years, but if you don’t have a good team at the track, you will not be successful. Racing a streamliner vehicle is a lot of busy work. You have to make sure the battery is fully charged, the ice water tank is full, the tires have the right pressure, all nuts and bolts are tightened, and a gazillion other little things. Because we cannot afford to pay anybody, the pit crew is all volunteers, and they are awesome! Without them, we wouldn’t have set any world records.

Mother Nature – the ultimate decision maker

No matter how well-prepared you are, if it is raining, you are not going to race. The Bonneville Salt Flats are perfectly flat, and they get flooded in no time. The water on the surface immediately turns into saturated brine, corroding and destroying pretty much everything. Most of the 2013 racing season was rained out. It rained a lot in 2014 as well, but we lucked out with the weather at the events we had signed up for. We set a new world record at 240.726 mph and setting a top speed of 270.224 mph. This made KillaJoule to the world’s fastest electric motorcycle, the world’s fastest sidecar motorcycle, and it made Eva the world’s fastest female on (in?) a motorcycle.

SUMMARY OF SPECS:

Battery: A123Systems Lithium Nano-Phosphate, 400 V and 10 kWh. 500+ HP.

Motor: EVO Electric AFM-240 motor, 500 HP.

Motor controllers: Two Rinehart Motion Systems PM100 controllers, 400 HP together.

Weight: about 1540 lb. (700 kg) including the rider Eva Håkansson

Dimensions: Length 19 ft (5.6 m), width appr. 21 inches (0.53 m), height appr. 38 inches (0.96 m), wheelbase 150 inches (3.8 m), track width when fitted with sidecar 45 inches (1.14 m)

Frame and suspension: Chrome-Moly steel tubing with “Springer” style front end and classic stereo suspension for rear end.

Brakes: Disc brakes front and back. Two ribbon brake parachutes, actuated with Bimba air cylinders.

Body: Fiberglass composite nosecone, canopy and sidecar wheel cover made by Nova Kinetics Aerosystems in Flagstaff, AZ. Body panels of aluminum.

Rider, builder, designer and owner: Eva Håkansson

Crew chief, designer and owner: Bill Dubé

Senior adviser and designer of the suspension: Sven Håkansson

Current record (as of August 2016): World’s fastest electric motorcycle at 248.721 mph (400.278 km/h). Complete list of records here.

Registered top speed: Currently 434 km/h 270.224 mph (as of June 2018).

“Fuel”: The battery in KillaJoule is recharged using wind power at home in Colorado, or by a hybrid quiet bio-diesel powered generator from CumminsOnan at the race track. We would love to use solar panels at the track, but we can’t afford it…

Follow Eva and the building of KillaJoule here on ScienceEnvy.com and on our Facebook page www.facebook.com/EvaHakanssonRacing

Do you want your name on the KillaJoule or Green Envy?

The KillaJoule wouldn’t have been possible without our great Partners and Sponsors! Do you want to be part of the KillaJoule team, or support our next effort “Green Envy”? Do you want your name or logo on the bikes blasting across the salt flats? Learn more here!

——

Published July 7, 2018